- Home

- Jeffrey Mariotte

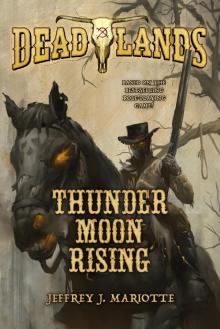

Deadlands--Thunder Moon Rising

Deadlands--Thunder Moon Rising Read online

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

About the Author

Copyright Page

Thank you for buying this

Tom Doherty Associates ebook.

To receive special offers, bonus content,

and info on new releases and other great reads,

sign up for our newsletters.

Or visit us online at

us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup

For email updates on the author, click here.

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you without Digital Rights Management software (DRM) applied so that you can enjoy reading it on your personal devices. This e-book is for your personal use only. You may not print or post this e-book, or make this e-book publicly available in any way. You may not copy, reproduce, or upload this e-book, other than to read it on one of your personal devices.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

This book is dedicated, with the greatest appreciation and respect, to Gordon D. Shirreffs, who never knew the numerous ways his novel Mystery of the Haunted Mine affected my life, and to Sidney Offit, who does have a sense of The Adventures of Homer Fink’s impact on me. Anybody who says a single book can’t change one’s life doesn’t know how to read a book.

Also, to Marcy, with love.

Acknowledgments

Inspiration is a funny thing, often coming around only when you’ve stopped looking for it. And anything as complex as a novel is born of dozens of inspirations, large and small. Some inform the whole work, others just a piece here, a character there.

Inspirations for this work include—but are by no means limited to—songs recorded and/or composed by Jimi Hendrix and Derek and the Dominos, Brian Wilson and The Beach Boys, The Rolling Stones, and Mark Lindsay. The work of the veterans’ service organizations The Mission Continues and Team Rubicon played a vital role, too. Also inspiring and important were the works of dear writer friends James Lee Burke and Marsheila Rockwell, who also assisted with research.

Various reference books and museums were consulted for the historical aspects, including the Fort Huachuca Historical Museum at Fort Huachuca, Arizona, and the Tucson Rodeo Parade Museum and the Museum of the Horse Soldier in Tucson, Arizona. Any mistakes or reinterpretations of history (particularly crucial in this work, since Deadlands is not history as we know it but as it might have been) are my own.

The Deadlands publishing program would not exist without Shane Hensley, Matt Cutter, and the gang at Pinnacle Entertainment; C. Edward Sellner, Charlie Hall, and the Visionary Comics crew; Tom Doherty, Greg Cox, Stacy Hill, Diana Pho, Patty Garcia, and the amazing team at Tor; Jim Frenkel; and Howard Morhaim; and they all have my deepest appreciation. Thanks are also due to pals Jonathan Maberry and Seanan McGuire for joining me in this incredibly rich sandbox to play with the toys.

It is, alas, chiefly the evil emotions that are able to leave their photographs on surrounding scenes and objects and whoever heard of a place haunted by a noble deed, or of beautiful and lovely ghosts revisiting the glimpses of the moon?

—ALGERNON BLACKWOOD

PART ONE

Cutting Sign

Chapter One

Tucker Bringloe remembered his mother as a grim-faced woman with thin lips. Small black eyes floated on her graceless visage like bloated deer ticks that had landed there accidentally. She almost never smiled, in his memory, though there had been one occasion, when she’d been passing a kidney stone, that he had mistaken a spasm of pain for an expression of delight. His father said that when she was a young girl, she had shot her older brother to death with their father’s rifle, in the false belief that he was a savage Indian. Tuck knew his father doubted her version of that story, since, as he’d said, “They lived in downtown Rensselaer, New York, at the time. Probably weren’t no savages within twenty mile, and not any reason for one to bother her if they was.”

A couple of years after that, Tuck’s father had come home drunk from a barn dance, and had made suggestions to his wife that she had forcefully declined. When Tuck woke the next morning, she was sitting on their bed, using a needle and heavy black thread to try to stitch up a gaping hole in the man’s throat. His body was limp and gray, and bed, father, and mother were all soaked in blood. One of his mother’s carving knives was on the floor beside her feet.

“He was ornery,” she explained. “Ill-mannered and grabby. But never you mind, he’ll be fixed up directly.” And so saying, she had met his gaze with those black buttons of hers, and her face had split into what he guessed had to be the first smile it had ever tried on.

It was ghastly, and he never forgot it.

But that wasn’t what drove him to drink. Instead, it was a memory that mostly came back to him when he had been drinking and drove him to drink still more.

He had reached that stage. He slouched in front of the polished wooden bar in a saloon called Soto’s, fingering his empty glass. Jack O’Beirne, the barkeep, glanced his way, and Tuck tapped the rim.

“Got to see some coin,” Jack said.

Tuck swore and dug into the pockets of his tattered Union army coat. In the right one he found lint and some kind of sandy grit and an old piece of blue glass polished by weather that he had found once and thought pretty enough to keep. One day there would be a child, or a woman, someone he’d want to give something to.

He held out empty hands and caught a glimpse of himself in the mirror behind the bar: dark hair matted and askew, eyes so bloodshot he could see red from here. Pathetic. He looked away. “One for the road?”

Jack’s thick black brush of a mustache twitched. “Got a dime?”

“No.”

“Half-dime gets you a beer.”

Tuck’s hands clenched into fists. “I don’t have it!”

“You’re done, mister.” The barkeep jerked his head toward the door.

His dismissive tone riled Tuck, but there was nothing to be done. Maybe he’d be able to scrounge up a coin or two somewhere. Sometimes one fell onto the floor around the poker tables, or he could snatch one from the piano player’s cup when no one was looking.

Tuck swiveled away from the bar, stumbled, and caught his balance by grabbing the back of a chair. A cowhand was sitting there with a big redhead on his lap, and when Tuck’s hand fell on the chair, the man shot him an angry scowl. The redhead was whispering something in his ear and grinding on him, though, and he didn’t say anything.

For an instant, Tuck wondered if he should start something. The man was wearing a pistol. If he would draw it and plant a couple of slugs in Tuck, it would free him of his mother and the war and all the other things that haunted his every hour, asleep or not, except when drink stilled those ghosts for a few hours.

The man turned his attention back to the whore on his lap. Tuck wasn’t even worth five seconds of his time. The worst part was, he couldn’t argue with the cowboy’s assessment. To shoot him would be to waste a bullet, because everything inside him that had ever been any good had died long ago. He would figure it out and fall down, one of these days, and that would be best for everyone.

He took a last look at the saloon. Above the piano was a bad painting of a nude woman who would have needed her backbone removed to pose the way she was. Senora Soto, who owned the place, sat at her usual spot in the corner, a drink in front of her and a revolver next to it, in case anybody tried anything funny with one of her girls. Two tables were crowded with poker players, and others with men there for the drink or the women or both. Some men sat alone or in quiet pair

s, brooding and glum, but at most tables, people laughed and carried on as if they were having a good time. Maybe it was a good time lubricated by alcohol and maybe not, but everybody looked happier than he did.

Probably this wasn’t the right place for him, after all.

Probably no place was right for him.

He breathed in the sweat and smoke and spilled beer and damp clothes, and walked outside into a downpour.

The drinks and now the rain conspired to remind him that his bladder needed emptying. He followed the boardwalk to the end of the block and stepped off into the muddy road. He had been in Carmichael for three weeks now, and Maiden Lane had been soup the entire time. He’d heard that the Arizona Territory was hot and dry, but was coming to think there must be two Arizonas. This one was hot, but the rains came almost every afternoon, drenching the town. By the time he had staggered back to the alley behind the saloon, he was soaked to the skin.

Between the clouds and the rain and the unpainted staircase to the floor above the saloon where Senora Soto’s girls had their cribs, no moonlight leaked through. Tuck could have pissed in the street, and maybe found himself a warm, dry bed in one of the marshal’s cells. But there were women in town. Kids, too, though not many. And as low as he had sunk (and that was very low indeed; Tucker Bringloe could have slid under a rattlesnake’s belly without scraping), he hadn’t lost every last ounce of the part of himself that had once been a Union officer. A warm bed was one thing, but was it worth the degradation of his last shreds of decency?

He put out one hand and gripped the back of a stair tread, to stay more or less upright while he relieved himself. When he was nearly done, a peal of thunder echoed off the walls and lightning lit the world with the sudden brightness of a thousand lanterns all uncovered at once, then closed again before the reality of it had set in. Tuck lost his grip on the stair, but caught it again before he fell into the mud that sucked at his boots.

As he put himself away and righted himself, he heard a footfall on the staircase above, and he realized that at the moment the thunder clapped and the lightning released its blinding glare, someone must have come out the door and started down. Tuck had faced Confederate soldiers with bayonets, had led his men into cannon fire, had taken a minié ball in his left arm and watched an untrained medic dig it out with a rusty blade. And he had seen much, much worse, sights he didn’t like to admit were taken in by his eyes rather than constructs of the part of his mind that spawned nightmares.

But at this moment, swaying, barely able to remain upright, absolute terror gripped him. The man descended at a steady pace, neither fast nor slow. With every soft rasp of those boots against the stairs, an icy grip tightened around Tuck’s heart. When the man’s feet were even with his head, an odor like nothing Tuck had ever experienced enveloped him, soaking through his clothing like the rain. He worried, for a moment, that it was the last thing he would ever smell; that even if he lived through the next two minutes, the stink would never release him.

Then the man was off the stairs. He swung around and walked past Tuck, his steps as easy as if the alley floor had been bone-dry. Tuck tried to look away, but the man’s eyes trapped his gaze; they seemed to glow with their own yellow light. Then lightning flashed again, brighter than before. In that instant, Tuck had a clear view of the man’s face. He had sharp-edged features, a prominent nose, a heavy brow, a solid jaw. A wide-brimmed hat kept the rain from his face, though Tuck had the idea that rain might stay away from him anyway, just on general principle.

And even in the light, those eyes were hot and yellow as flame.

Tuck grabbed the stair again. His legs had started to tremble, his knees nearly giving way. The man strode quickly to the end of the building. When Tuck’s legs felt sturdy enough to carry him, he followed. Reaching the corner, he saw the man again, mounted on a black mare with a white blaze on her snout and eyes almost as yellow as her rider’s. Only this time—and Tuck was happy to blame it on the darkness and shadows—the rider’s face had changed, and his hands, too. He had appeared human, on the stairs. But now his features seemed to have disappeared, so that his face was an indistinguishable dark mass, and his skin was black. Not dark brown, like the free men he had known, and those who had not yet been free who he’d fought to liberate in the war, before the Confederacy had taken that step and the war had turned on other issues, but black like ink, like jet, like the darkest hour of a moonless night. The man tore past Tuck without sparing him another glance. Lightning flared once more, revealing horse and rider galloping past the Methodist church, which perched just outside of town, as if afraid of contamination had it dared venture nearer. Then the light was gone, and so was the man.

When he was gone, Tuck felt the rain pummeling him again, as if it had paused while the man was in sight but now returned with redoubled force. Wind-driven drops pelted him, stinging. He hurried for the protection of the overhang above the saloon’s doorway, where the upstairs balconies faced onto the street, where Senora Soto’s girls sometimes came out to call to the town’s menfolk. He would not be welcome inside, but at least he could shelter under the overhang for a few minutes. Maybe the rain would end as suddenly as it had begun.

He had barely made it out of the weather when he heard screams from upstairs.

Chapter Two

Instinct took over and he pushed through the door. The odor made him crave a drink, but he had no more money than before, and now he was tracking mud and dripping rainwater on the plank floor. People were moving toward the staircase—Senora Soto, for one, clutching her revolver, her dark face tight with worry. At the top of the stairs, one of her crib girls stood with both hands on the banister, wearing only ruffled bloomers. Tears glistened on her cheeks and her mouth hung open. Screams issued from behind her.

The scene was chaos, barely controlled. Tuck couldn’t make out any words in the overall din, until someone upstairs shouted, “Somebody cut Daisie!”

At that, there came a moment’s stillness in the saloon, an unnatural silence. It just lasted for a second, then broke all at once. Men rushed the stairs, some drawing guns. Tuck started checking the tables and floors for stray coins, but then a terrible thought struck him and he wove through the crowd, shoving some men aside in his hurry to reach the stairs. The storm, the strange man on the stairs, and the palpable fear in the air had all conspired to sober him. He forced his way through the clot at the top of the stairs, past the half-naked woman. Others filled the upstairs hallway, and Tuck wove through them.

Senora Soto stared into one of the cribs. The revolver looked enormous in her small fist.

“Who did this?” Senora Soto demanded. “Who?”

“I don’t know,” one of the women said. “I never saw him.”

Senora Soto asked the question again, and each woman responded in kind. Nobody knew, nobody saw a thing.

“I want that calico dress of hers,” one said. “I always thought it’d fit me better than it did her.”

“Oh, you hush up,” another replied.

“Well, it would.”

Tuck couldn’t hold himself back any longer. He feared what he might see, but was more afraid, for reasons he could not elaborate and didn’t care to try, of not seeing it. Senora Soto had abandoned her place at the door, so Tuck peered inside.

A woman lay on her back, her head and shoulders and arms hanging off the bed, on the side facing the doorway. Blood covered her neck and face, dripping from her chin and forehead onto a braided rug on the floor. Pink and gray and brown blobs—organs, Tuck guessed—dangled from her middle.

Her sternum had been slashed open, almost to her throat.

The odors of blood and bodily fluids and urine assaulted his nose, and Tuck’s stomach heaved. He gripped both sides of the jamb to steady himself. He had seen that one, Daisie, in the saloon. She had always been pleasant enough, not dismissing him because of his drunkenness, his filth, his poverty. She had been decent, and now she was dead.

A chill caught hi

m and he shuddered. He was soaked to the bone, so that was no surprise, but this came from a deeper place than that, as if freezing him from the inside out. Underneath the other smells in the room he noticed a stink, sour and rotten, that he had encountered before. Just minutes earlier, by the stairs.

“I know who did this,” he said. No one heard. One man nearly knocked him down, angling for a better view of the poor woman’s corpse.

“Ohh,” the man said. “If that don’t beat…”

He didn’t finish his sentence, or Tuck didn’t hear the end of it. He released the doorjamb and said it again, louder. “I know who did this!”

Finally, his words broke through the din. Senora Soto halted her interrogations and faced him.

“Who?”

“I don’t know who he was,” Tuck said. He could tell he was slurring his words, but not as much as he might have ten minutes earlier. “I saw a man go down the back stairs, couple minutes ago. Something about him that didn’t set right with me.”

“Where is he, then?”

“He took off on a big black horse. White streak on the muzzle.”

“How do we know he ain’t done it?” one of the men asked. “He’s wet. He coulda gone out and downstairs and come back around, just to throw us off.”

“Anybody know him?” another one asked. Tuck realized it was the cowhand from downstairs, the one who’d had a redhead on his lap. “Can anyone speak for this drunkard?”

“I seen him around,” someone said.

“How would he get the money to go with Daisie?” one of the women put in. “He has to beg for drinks.”

“Look at him,” another said. “Daisie would never have gone upstairs with such as him. She has standards.”

“I saw this one in the saloon earlier,” Senora Soto said. “After Daisie went upstairs. He is not the one.”

Deadlands--Thunder Moon Rising

Deadlands--Thunder Moon Rising